Mentor. Scientist. Iconoclast. Believer.

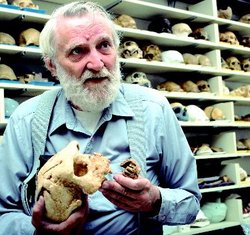

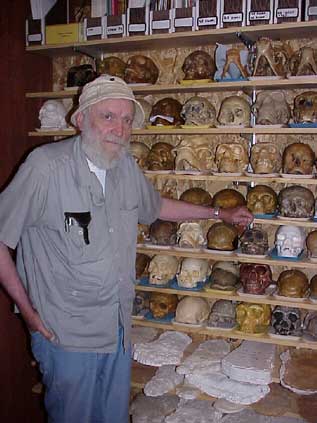

If you studied anthropology at Washington State University in the late 20th century, there’s a name you likely won’t forget: Dr. Grover Krantz. Or just “Grover,” as he insisted everyone call him.

To many, he was a brilliant academic mind—a tenured professor, rigorous researcher, and a man with a deep understanding of human evolution. To others, he was that professor who believed in Bigfoot. And he did, whole-heartedly.

But Grover Krantz wasn’t some fringe scientist chasing shadows in the woods. He was a respected anthropologist who dared to apply real scientific methodology to one of the most controversial creatures in folklore: the North American Sasquatch (and its Himalayan cousin, the Yeti). While many dismissed cryptozoology as pseudoscience, Grover stood firm in his belief that Bigfoot could, and should, be studied with the same discipline and curiosity we afford other evolutionary relics.

He authored multiple books on the subject, drawing not from legend, but from evolutionary biology, anatomy, and fossil records. He saw footprints not as hoaxes, but as biomechanical puzzles worth analyzing. Grover didn’t ask his peers to believe—he asked them to look.

🚬 Cigarettes, Casts, and Cryptids: Learning from Grover

I had the rare privilege of not only sitting in his class but also working side-by-side with him. And let me tell you—being in Grover’s lab felt like stepping into a living chapter of scientific folklore.

The air was always thick with the haze of his hand-rolled cigarettes—each one a tiny ritual. You’d hear the crinkle of tobacco paper between his fingers before the scent drifted through the room, blending with plaster, aged bones, and mystery. His beard—long, coarse, and sun-kissed with a yellowish tinge—looked like it had stored decades of field notes and forest whispers.

And that voice—gravelly, deliberate—would deliver lessons in evolutionary theory just as easily as it would pivot into an impromptu monologue about bipedal primates in the Pacific Northwest. He didn’t teach so much as transfix.

I can still see us, elbow-deep in skeletal casts and archaeological puzzles, while he grumbled about academia’s resistance to “uncomfortable ideas”—all while gently correcting your grip on a femur or explaining the structure of a primate foot.

It wasn’t just a class. It was a masterclass in thinking for yourself—even if it meant walking alone.

🐾 A Legacy Carved in Bone (Literally)

One of the most touching, and quintessentially Grover, parts of his story came at the very end.

He donated his body to science with one request: to be reunited with his beloved Irish Wolfhound, Clyde. Today, Grover and Clyde stand side-by-side at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History—skeletal companions immortalized together in one of the most hallowed halls of scientific history. It’s the kind of quirky, poetic ending that Grover himself would’ve appreciated.

It’s also a reminder that science isn’t just about numbers and theories—it’s about stories, relationships, and the pursuit of truth, no matter how wild the trail.

🌲 The Man Who Walked With Sasquatch

Grover Krantz wasn’t just a scientist who believed in Bigfoot. He was a scientist who believed in curiosity without borders, in challenging orthodoxy, and in the importance of asking “what if?” even when the room falls silent.

He mentored countless students—myself included—not only in anthropology but in how to approach the world with wonder, humor, and just the right amount of rebellion. Grover taught us that the line between myth and science isn’t always as thick as we think. And that maybe, just maybe, the real discovery lies in having the courage to explore it.

Here’s to Grover.

Here’s to curiosity.

Here’s to the Yeti.

Yeti Lives.

If you enjoyed this story, feel free to share it or leave a comment below. Have your own wild professor tale or Bigfoot encounter? I’d love to hear it.

👣 Stay curious, friends.

Leave a Reply